by Anne White

In Arnold Bennett's 1910 book How to Live on 24 Hours a Day, he proposes that novels should be excluded from serious reading. Now, everyone, keep your literary shirts on while Bennett gives his reasons:

1. Bad novels ought not to be read in the first place, so they're ruled out.

2. "A good novel rushes you forward like a skiff down a stream, and you arrive at the end, perhaps breathless, but unexhausted. The best novels involve the least strain."

3. It is only the bad parts of [otherwise good] novels that are difficult.

4. If you're working hard at learning to think better, read more deeply, dig more skillfully, it seems (according to Bennett) that all of that inspiration is going to require a bit of perspiration. Novel reading (in his terms) is just a bit too much fun! He says, "You do not set your teeth in order to read 'Anna Karenina.' Therefore, though you should read novels, you should not read them in those ninety minutes [of serious reading]."

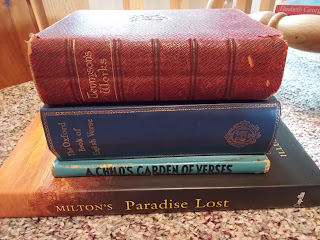

What sorts of books do qualify then? Bennett mentions history or philosophy, but he has a preferred alternative for beginners: poetry.

Imaginative poetry produces a far greater mental strain than novels. It produces probably the severest strain of any form of literature. It is the highest form of literature. It yields the highest form of pleasure, and teaches the highest form of wisdom. In a word, there is nothing to compare with it. I say this with sad consciousness of the fact that the majority of people do not read poetry...Still, I will never cease advising my friends and enemies to read poetry before anything.

How should we start? Here are Bennett's suggestions:

1. William Hazlitt's essay "On Poetry In General," which you can read here. Why? Here's Bennett's review: "It is the best thing of its kind in English, and no one who has read it can possibly be under the misapprehension that poetry is a mediaeval torture, or a mad elephant, or a gun that will go off by itself and kill at forty paces. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine the mental state of the man who, after reading Hazlitt's essay, is not urgently desirous of reading some poetry before his next meal." A warning: it's fifteen pages long, so pour yourself a large cup of something first. Here's a short excerpt:

We are as prone to make a torment of our fears, as to luxuriate in our hopes of good. If it be asked, Why we do so? the best answer will be, Because we cannot help it. The sense of power is as strong a principle in the mind as the love of pleasure. Objects of terror and pity exercise the same despotic control over it as those of love or beauty. It is as natural to hate as to love, to despise as to admire, to express our hatred or contempt, as our love or admiration. "Masterless passion sways us to the mood / Of what it likes or loathes."

2. Next, try reading some "purely narrative poetry." Bennett suggests Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Aurora Leigh, which (he says) is a novel written in poetic form, and which you can read here. Here is his advice:

Decide to read that book through, even if you die for it. Forget that it is fine poetry. Read it simply for the story and the social ideas. And when you have done, ask yourself honestly whether you still dislike poetry.

Here is an excerpt of Aurora Leigh to whet your appetite:

I, Aurora Leigh, was born

To make my father sadder, and myself

Not overjoyous, truly. Women know

The way to rear up children, (to be just,)

They know a simple, merry, tender knack

Of tying sashes, fitting baby-shoes,

And stringing pretty words that make no sense,

And kissing full sense into empty words;

Which things are corals to cut life upon,

Although such trifles: children learn by such,

Love’s holy earnest in a pretty play,

And get not over-early solemnised,—

But seeing, as in a rose-bush, Love’s Divine,

Which burns and hurts not,—not a single bloom,—

Become aware and unafraid of Love.

Such good do mothers. 3. And after that? Bennett recommends that apprentices in serious reading should take, oh, about a year to build up muscle on such poetry. Then we'll be "fit to assault the supreme masterpieces of history or philosophy. The great convenience of masterpieces is that they are so astonishingly lucid."

4. Of course, reading some Arnold Bennett wouldn't hurt either. Or maybe he'd be rated as too much fun.

What do you think about this literary "no pain, no gain?" Have you read Hazlitt's essay, or Aurora Leigh? Do you agree that good novels should whish you along the mental stream without effort, or is Bennett perhaps not giving writers of prose (including himself) enough credit?

No comments:

Post a Comment